By Alex C. Maccaro

Image 1: Thomas Eakins – Swimming, 1884. Oil on canvas. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX

Male Desire: The Homoerotic in American Art, written by the painter and art critic Jonathan Weinberg, is a survey of how the male body has been portrayed from the late nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth century. In this book, which is broken up chronologically into seven cleverly titled chapters, Dr. Weinberg not only presents examples of homoerotic images of the era, but he also relates the images to the culture of American society at the time. His purpose is to show how changing values and moral norms were reflected in the homoerotic images that many straight and gay male artists were producing. Placing his text within the realm of the up-and-coming field of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) studies, Dr. Weinberg argues that the suggestive image of the male body has been burdened with sexual overtones throughout history, but it has carried different meanings in different eras. Homosexual and homoerotic content, he proposes, is by no means always conscious in images. I think that Dr. Weinberg’s book is a well-designed and beautifully written work. That said, I do question whether some of the images he discussed should have been included.

Dr. Weinberg defines the term “homoerotic” as concerning or arousing sexual desire centered on a person of the same sex, even though he acknowledges that this term is difficult and vague and that it can “suggest the possible desirability of a man for another man, without equating those desires with stereotypical conceptions of late twentieth-century sexual identities.” (p. 9) All of this in mind, in Male Desire, he presents a concentrated overview of art centered on these themes. After a concise but informative introduction that explains an overview of his text, Dr. Weinberg delves into a survey of homoerotic art in all forms, from painting and illustration to sculpture to photography. In each of the seven chronological chapters, among them “Water,” “The Man in Uniform,” “I Want Muscle,” and “The Age of AIDS,” he discusses the evolution of technique, the shifting social approach to male art, and individual artists who created homoerotic works, supported and advocated for them, or both. As history advanced from the late nineteenth century through the twentieth century, writes Dr. Weinberg, the depiction of the male body in art changed and became less veiled and more explicit.

As he explains, while earlier artists such as George Bellows or Thomas Pollock Anshutz framed appreciation of the male body within the tableau of sports, labor or history, more contemporary artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe and David Wojnarowicz openly celebrated homosexual identity and male nudity. In the mid-twentieth century, for instance, a new sense of gay identity was developing amidst scrutiny and controversy, and Weinberg illustrates this concept by exploring examples like the witty paintings of Paul Cadmus, the contentious works of Jasper Johns (in particular, Target with Plaster Casts), and Harold Stevenson’s monumental The New Adam. These are all explored within the context of historical events and moments such as the publication of the Kinsey Reports and the targeting of homosexual men through McCarthyism. Overall, in his book, Dr. Weinberg makes unusual but thought-provoking socio-historical connections between works of art that celebrate the male body and the changing political and societal norms.

Dr. Weinberg’s book judiciously contextualizes and explores complex concepts within the realm of LGBTQ cultural studies. As he notes, however, the book is not a history of LGBTQ art; rather, it demonstrates the extent to which same-sex desire inspires and influences American visual culture. In fact, the author sometimes even identifies images by heterosexual artists that have some homosexual interest. In other words, according to Dr. Weinberg, several of the works that he discusses could be read as appealing to same-sex desire, but the author writes that the homoerotic functions “to widen the discussion so that the question of an artist’s sexual identity is only one possible context that might explain a work’s erotic context.” (p. 9) A noteworthy example is Thomas Eakins’s 1884 Swimming (Image 1); although the act of swimming in the nude could lead to sexual contact and Swimming may as well depict fraternal and shameless camaraderie among young men, the painting more so reveals Eakins as a realist and an exhibitionist who opened up the possibility of viewing these nude young men to both male and female fantasies.

In addition, Dr. Weinberg writes in a tone that is authoritative but accessible to the non-scholarly reader, and his book reads easily like an intriguing novel rather than an academic art discourse. He plays his skills as an art critic and as a painter to an advantage. As the former, he expresses abstract and multifaceted concepts in a direct and clear manner, and he enhances our appreciation of the subject by commenting on each artist’s technique. This commentary also reflects his proficiency as a painter, and, as an artist, he shows his capability of visual analysis in his writing.

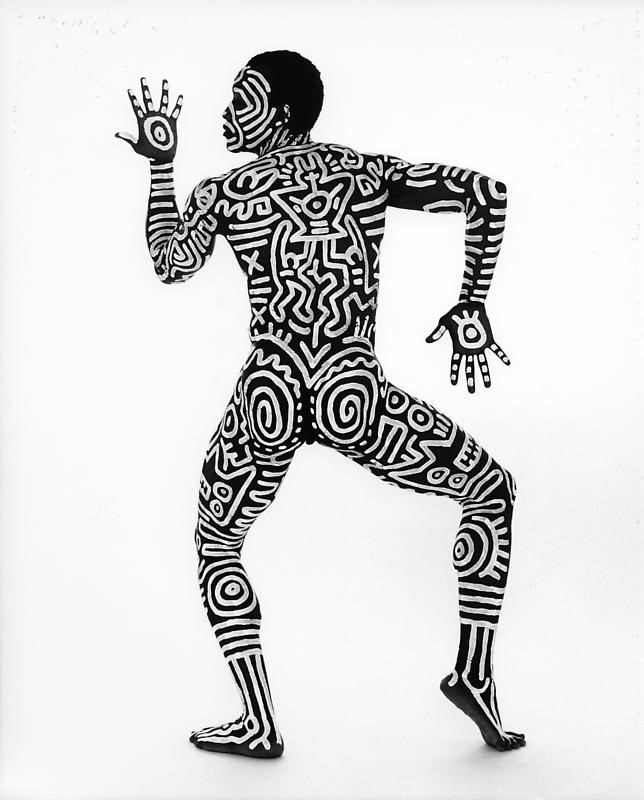

Image 2: Keith Haring – Fight AIDS Worldwide, 1990. Lithograph. Keith Haring Foundation, New York.

However, although Dr. Weinberg’s book provides a good basis for future explorations of the subject and persuasively covers an emerging scholarly subject through a wide historical spectrum, there are flaws to his study. Even though he finds much more homoeroticism in American art than the reader and viewer might expect, I think that the homoerotic nature of some works that Dr. Weinberg describes just simply isn’t there. For example, Dr. Weinberg may be overanalyzing an untitled conceptual billboard by Felix Gonzalez-Torres from 1991, which depicts a photographic image of an empty bed with two pillows. While the bed may imply a mark a lover has left behind, I do not find the imagery to be erotic or sensual. The inclusion of this image goes against the linearity of Dr. Weinberg’s discussion of a progression to more openly sexualized imagery. Also problematic is the inclusion of Keith Haring’s 1990 lithograph Fight AIDS Worldwide (Image 2), which depicts Haring’s signature figurations stacked upon a large figure. To me, although some of Haring’s works - such as his 1983 body paintings on a nude Bill T. Jones (Image 3) - evoke more explicit eroticism, this work does not.

Image 3: Keith Haring – Bill T. Jones, 1983. Ink on photographic paper. Keith Haring Foundation, New York.

Image 4: John Patrick Dugdale – Nameless Lissisitude, 1999. Cyanotype Photograph. Private Collection.

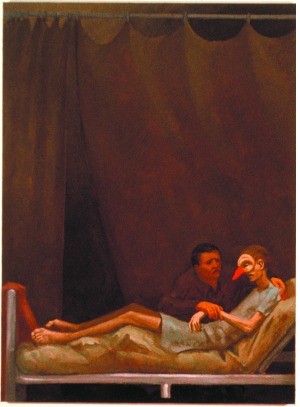

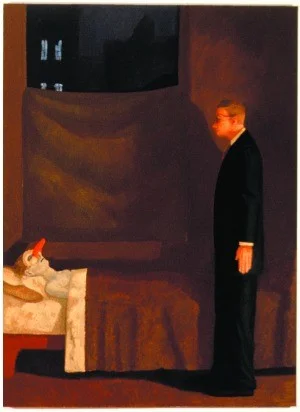

In fact, Dr. Weinberg’s weakest chapter concerns art during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s. This chapter is uneven at times, and the author’s thesis isn’t illustrated as clearly here. As I mentioned in his exploration of Gonzalez-Torres’s billboard, the AIDS crisis chapter incorporates several examples that he overanalyzes in the context of homoeroticism and sexuality. Some of the images included in this chapter, like John Patrick Dugdale’s 1999 nude self-portrait Nameless Lissisitude (Image 4), do depict sensualized bodies and can be read as sexually stimulating and homoerotic. Yet the inclusion of Patrick Webb’s 1992 Lamentation of Punchinello/By Punchinello’s Bed (Image 5) is unnecessary and irrelevant to Dr. Weinberg’s discussion. These paintings, which depict an emaciated young man on his deathbed as another man (presumably his lover) mourns his companion’s impending death, are grim and symbolize the harsh realities of the AIDS crisis.

Image 5: Patrick Webb – Lamentation of Punchinello / By Punchinello’s Bed, 1992. Oil on linen. Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, New York.

Image 6: Mark Morrisroe – Untitled (Self-Portrait), 1989. T-665 Polaroid. Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection), Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland.

I would not say that these images are homoerotic or that they can be read as sexually stimulating. Even though I do understand Dr. Weinberg’s motive of exploring the homosexual experience during troubling times and I do think the discussion of the AIDS crisis is crucial to the discourse on LGBTQ studies, I simply do not see the appeal to one’s erotic senses of viewing a painting of a sickly individual dying. Nor would I become aroused by Mark Morrisroe’s 1989 photograph Untitled (Self-Portrait) (Image 6), in which he does appear bare and nude but also appears gaunt and ill. In this sense, perhaps Dr. Weinberg may be diverging from the subject of the homoerotic and may be imbuing a bias that he could hold; after all, several of his artist friends did succumb to the AIDS epidemic.

Nevertheless, Dr. Weinberg’s book is a comprehensive, lavishly illustrated and intelligently written study on the homoerotic in American art history. It is a foundational text in the field of LGBTQ studies, and it sets a precedent for future writers on the up-and-coming field of American LGBTQ arts and culture. The objections that I raise to this book and the minor flaws of his text should not preclude an LGBTQ studies scholar or non-scholarly reader from searching out this book as a solid reference, although the text would best suit LGBTQ art historians for their research on this complex and increasingly relevant subject.

***

Weinberg, Jonathan. Male Desire: The Homoerotic in American Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2004 (208 pages).