By Christopher Heide

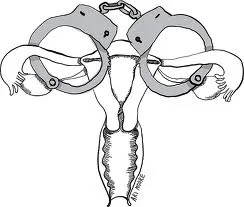

Forced sterilization, while not as widely publicized as abortion, is a highly controversial practice that seems intent on permeating itself throughout our society.

Alison Thorpe, a London mother, petitioned to have her severely disabled daughter's womb removed, in order to prevent the girl from experiencing the pain of menstruation.

While this mother's attempt to reduce her daughter's pain is most likely genuine, it can hardly be classified as humane.

A person's ability to sexually reproduce is an innate aspect of life. Removing it, even for medicinal purposes, is akin to brutal and primitive castration. It's completely adversative to the cultural and social refinement of modern society.

Just as with abortion, a person should have a right to choose how his or her body is treated. It is simply not right. This issue is black and white; no gray area should exist.

Some argue that the most despicable criminals, especially rapists, should not be allowed to ever reproduce. Surely, many rape victims would accept the castrations of their attackers.

However, even the most reprehensible individuals have a right to autonomy over their sexual abilities. This is not to say that depraved individuals should not be punished for their actions; they should be.

In some ways, forced sterilization is less humane than the death penalty, as the recipients of forced sterilization must live with the consequences of the actions taken against them. Freedom over one's body must always be protected, especially from the government.

The United States' moral entanglement with forced sterilization and the disabled is nothing new. More than 80 years ago, a Supreme Court decision upheld a state statute that required a mentally disabled woman to undergo sterilization procedures. In this case, Buck v. Bell, the court justified its decision as "for the protection and health of the state."

While this decision was later overturned, it illustrates an important point. People are often too willing to wash their hands clean of the mentally and physically deficient people in this world.

For Thorpe to suggest that such a painful procedure would be in the best interest of her daughter, Katie, is completely asinine. While Katie may not be able to make legal decisions for herself, that does not mean that her wishes should not be considered, nor does it mean that her body should not be protected.

It is merely the selfish attempt of a tired mother to alleviate her own pain instead of helping her daughter live with cerebral palsy.

Most agree that parenting is the most difficult job in the world, and parents often sacrifice much of their own lives in order to provide their children with a stable upbringing. Anything that can be done to eliminate these pressures should be done. However, there must be limitations.

"It is very difficult to see how this kind of invasive surgery, which is not medically necessary and which will be very painful and traumatic, can be in Katie's best interests," Andy Rickell, executive director of the disability charity Scope, told The Press Association. "This case raises fundamental ethical issues about the way our society treats disabled people and the respect we have for disabled people's human and reproductive rights."

The rights of disabled people deserve the same considerations as those of all other people. They must no longer be marginalized and ignored. For any other group of people, anything less would be considered unjust.

This case is akin to another sterilization that occurred in Seattle in 2004. The parents of a girl named Ashley had her reproductive organs removed, preventing Ashley from enduring puberty and entering adulthood.

"Ashley will be moved and taken on trips more frequently and will have more exposure to activities and social gatherings ... instead of lying down in her bed staring at [a] TV all day long," according to her parents.

They were trying to improve Ashley's quality of life by effectively keeping her a child.

While forced sterilization may be convenient for those surrounding a disabled person, it is unlikely that the disabled person, despite mental or physical limitations, would welcome such a painful and invasive procedure.

Convenience cannot triumph over human rights. The fact that these cases even exist is disturbingly indicative of our convenience-minded society. As cliché as it may sound, the right thing is not always the easiest to do.